Automated Loom Part II: the computer’s beginning

Within the textile industry, although the invention of the Jacquard loom marks a significant moment in history, it does not represent a singular moment in time. There was no sudden revelation of innovation, but rather a collective refinement of decades of failed work. Nonetheless, if we broaden our historical lens and view multiple decades as a singular historical moment, the Jacquard loom has indeed become one of the most influential inventions in our modern history. This week, we will look at how a piece of weaving equipment directly inspired the first computer, changing the way humans navigate through the world.

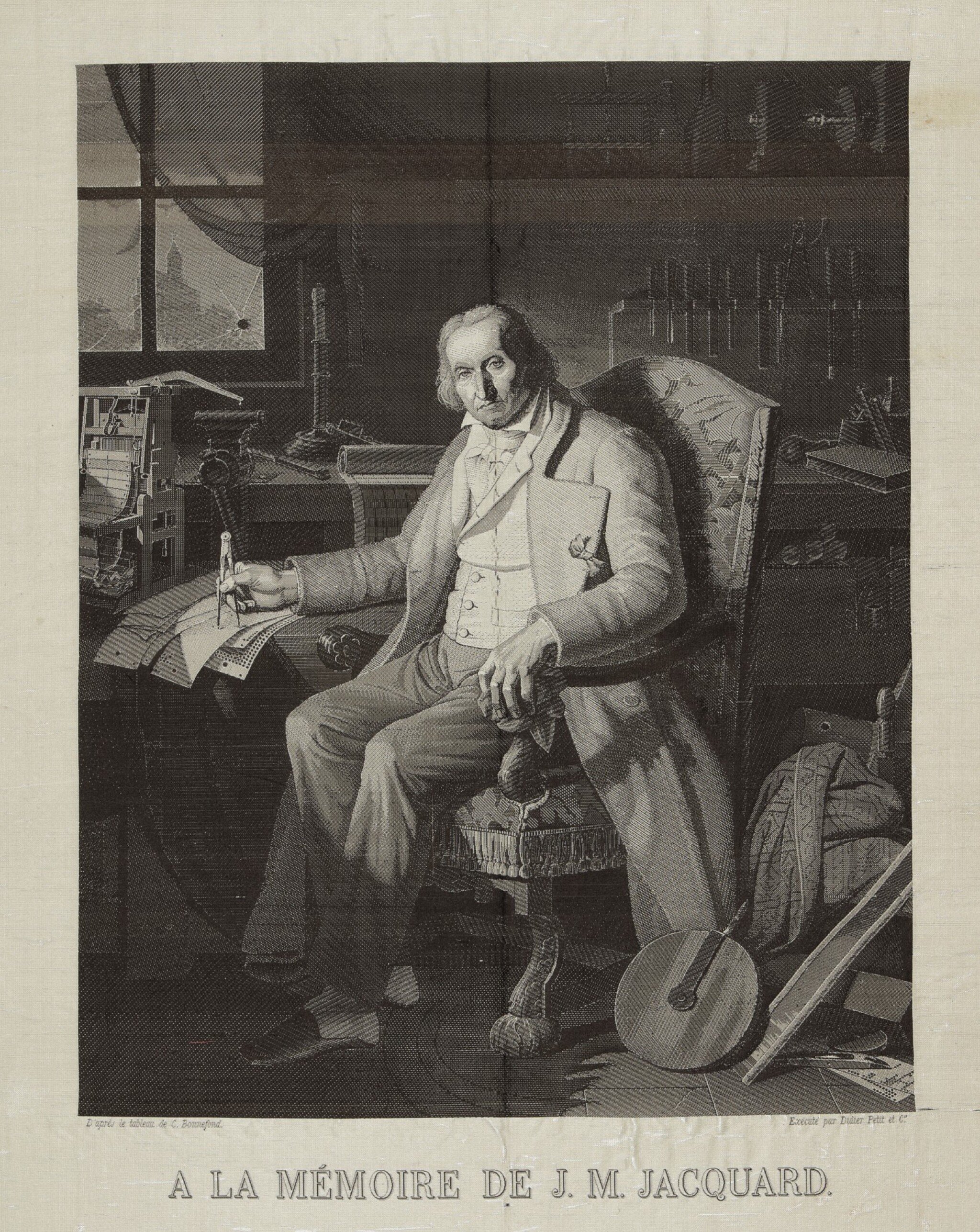

Joseph Marie Jacquard was born in 1752 in Lyon to a master silk weaver. As the son of a weaver, Jacquard was expected to carry on the profession, but as a young adult he had no interests in the weaving process. It was not until his father’s death when Joseph was left his father’s weaving workshop and was forced to carry on the family textile business. At this time, Jacquard started experimenting with several types of smaller weaving inventions. In 1803, he was summoned to the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers (National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts) in Paris, where he first encountered Vaucanson’s loom. Over the next few years, Jacquard was able to massage the kinks of Vaucanson’s invention, while combining previous disregard ideas from Flacon and Bouchon to publicly release his loom in 1805.

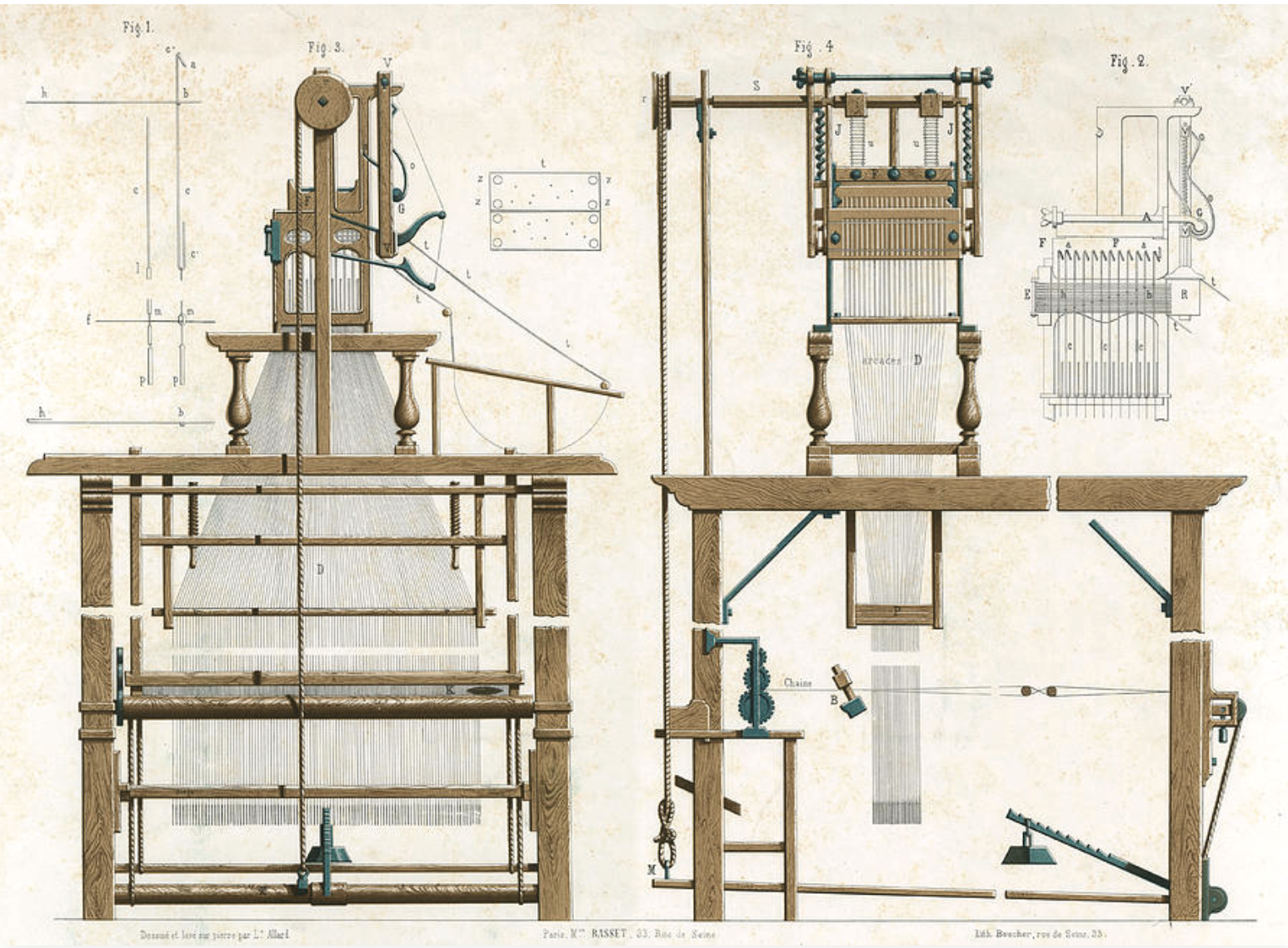

What differentiates Jacquard’s loom from previous contraptions was its ability control every single warp end- allowing for infinite structural and pattern flexibility. Vaucanson’s loom was a dobby loom controlled through a series of harnesses, it can hold between two to twenty-four harnesses. On the harness are a series of heddles (stiff wire with a loop opening) which hold each warp thread, and in turn control the warp movement. If a harness is lifted, the associated warp ends are raised. This type of loom limits the type of weave structure and pattern.

Alternatively, if a complex pattern needed to be woven, this process took place manually with a drawloom. A master weaver would operate the front of the loom controlling weft threads, while a draw boy operated individual heddles. The draw boy position was at times dangerous, sitting suspended above the loom, or hidden below all the moving parts.

Draw Loom with Draw boy

Jacquard was able to combine the flexibility of a drawloom with the punch card mechanization of Vaucanson and Falcon’s. The term jacquard refers not to the loom itself but to the lifting device and the system of automation. The punchcard system, which ultimately is the most influential aspect of the Jacquard Loom, is only one element to the looms success.

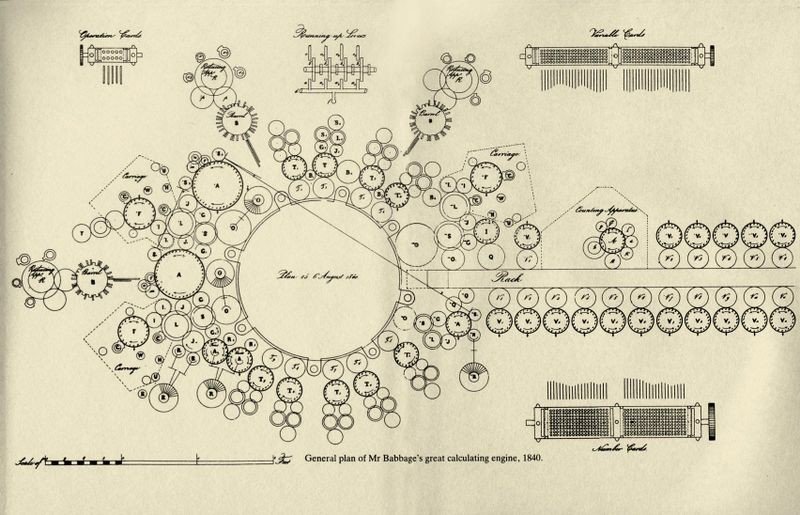

Although not solely his invention, Jacquard’s loom was by far the most successful loom iteration to date. Complex textiles were able to be woven with minimal flaws quickly with less human labor. To prove the loom’s ability, Jacquard wove a portrait of himself which was so detailed in required 24,000 punch cards as opposed to the average 4,000. It was this portrait that caught the eye of British mathematician Charles Babbage in 1819. Fascinated by the looms ability to store and produce vast amounts of information, Babbage appropriated both the punchcard system and the formal mechanics of Jacquard’s loom to create his own calculating machine. Rather than weaving fabric, the machine wove information and was able to take his Difference Engine and create the Analytical Engine. This new machine directly imitated both the punch card system as well as the metal rod/cogwheel mechanization.

The distinguishing factor of the Analytical Engine was its ability to hold memory, which becomes the direct link to modern computers today. Other machines with calculating ability were still unable to store input and output, the Analytical Engine’s distinguishing factor was its ability to hold memory. Much like the human’s mind memory capabilities, this becomes the direct link to modern computers today. Babbage understood the link between loom and human cognition and as a result defined human’s relationship to machine.

References

Essinger, James. Jacquard’s Web. (Oxford University Press, Oxford UK. 2004)

Robinson, Tim. “The Analytical Engine: 28 Plans and Counting,” Computer History Museum. December 08, 2015. https://computerhistory.org/blog/the-analytical-engine-28-plans-and-counting/