In the Frame

Drawing from the museological act of framing, the curator column “In The Frame” compiles images of objects, peoples, and architecture that are united by a common theme, project, or motif. The curator columnist, Delanie Linden is a PhD candidate in History, Theory and Criticism of Art and Architecture Department at MIT. She is inspired by the intellectual and creative happenings of the department and designs each column with the architecture community in mind. Her selection of subject matter is deeply motivated by her own artistic practice as an oil painter and her training as an art historian. The conditions of making, the contingencies of materials, and the artist's and beholder’s sensorial experience are the critical foundations of the column. Circumstances of making and materiality - from colonial trade networks and slavery to the fragility of matter - serve as the driving force of inquiry.

Proprioception

In this column, Linden discusses the role of proprioception in the experience of art. She cites the research of Dr. Elizabeth Browne, whose work examines eighteenth-century French sculpture.

Art relies on our bodies. To experience art in its multifarious dimensions, the (human) beholder uses one or more of the five senses: touch, sight, hear, smell, taste. Less discussed yet equally important is the role of ‘proprioception’ in the experience of art. Proprioception is an (often unconscious) perceptive phenomenon defined as the central nervous system’s internal awareness of the positionality of the body’s limbs.(1) Receptors signal the movement of our bodies in space and the “feeling” of someone or something near us.

Proprioception is vital to one’s experience of sculpture in the round, which beckons the viewer to walk around it. We rotate in relation to the physical presence of the sculpture, taking heed to come close but not too close. Proprioception registers the distance between us and the object. Goosebumps rise, hair stands. Like sculpture, canvases and panoramas hung on gallery walls, such as Night Revels of Han Xizai (12th c.) or Van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône (1888), require our bodies to move. To come close but not too close. To move along the surface’s edge, to stand up straight or crouch down.

Anonymous (after Gu Hongzhong, 10th century), Half-section of the Chinese painting Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, ink and colors on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm. 12th century remake from the Song Dynasty. Collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night Over the Rhône, 1888, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay.

In her dissertation "Modeling the Eighteenth Century: Clodion in the Ancien Régime and After," which was recently defended in MIT’s History, Theory, & Criticism program (2021), Dr. Elizabeth Browne states: “In eighteenth-century France, an artwork’s significance was understood through the relational engagement of the beholder with the work of art, the ways in which it appealed to viewers’ senses, imaginations, and emotions.” Though proprioception was coined much later in the early twentieth century, its theoretical precedence can be traced to the Enlightenment, and earlier. As Browne indicates, moving through space in a “relational engagement” with an artwork, was an important factor in one’s experience – and assessment – of an artwork’s overall significance.

Browne argues that the terracotta sculptures made by French sculptor Claude Michel, called Clodion (1738-1814), “embodied eighteenth-century theories of sensuous and imaginative perception.” Indeed, Clodion’s Intoxication of Wine (c. 1780-90) entices the viewer to walk up close, to circumambulate it.

With art, together, we dance.

(1). "proprioception." Oxford Reference. . . Date of access 17 Apr. 2021, <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100349984>

Memory

In this article, Linden interviews MIT HTC PhD candidate ElDante Winston, who discusses the role of architectural history in the preservation, making, and repositioning of cultural memory.

Memory is the yoke that binds history. It enjoins the experience of all organisms over time and space. Like the striations of archaeological layers, like the meeting of two people, like a footprint in mud, memory is the collision of past and present, many pasts and many presents.

From left: Philippe de Champaigne's Vanitas, c. 1671, oil on canvas, Musée de Tessé, Le Mans, France. Jean-Simon Berthélemy, Bust of Denis Diderot, oil on canvas, 1784, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe. Photo still from Christopher Nolan’s Memento, 2000.

Memory lives in numerous places: in the ruins of architecture, in the writings on walls, in pictures, and in our minds. It is both physical and immaterial, deeply buried and superficial, blurry and lucid. For the historian, remembering is twofold. As MIT HTC PhD candidate ElDante Winston asserts, “with the understanding that memory is shaped in the present time of recall, the historian must be aware of the temporal difference between the occurrence and the remembrance.” (1) Memory is reconstructive. Its very act is a process of editing the past. When, for example, one looks at the ruins of Rocca Galliera, the beholder of such history brings with them their own prior knowledge. It is a fusion of the old and new. As such, the temporal stance of the historian should play a larger role in the conversation of history. In other words, the historian’s past experiences are important when considering their version of history-making. One might conclude, following Winston’s suggestions, that the author is, in fact, not dead.

Image: Ruins of Rocca Galliera. A reminder of Bolognese Unity/The repression of Papal oppression.

Photo by ElDante Winston, MIT HTC PhD Candidate

Winston’s dissertation examines the role of memories in the history of architecture. More specifically, he is interested in the ways in which the collective memory of a given group of people is transmitted, be it oral, written and/or pictorial. He explores how “the contemporary architectural historian could reposition architecture associated with violence within the discourse of architectural history by thinking deeply about how the history of architecture relates to the memories and repressions associated with it.” Here, reposition is key. Memory is not only reconstructive, but it can be reconstructed. By recognizing the presence or absence of memories vested in architecture, historians of architecture can shed light on important facets of history and work to dislodge overarching narratives.

Graffiti on the inside walls of Église Saint-Paul in the Marais quarter of Paris, likely from c. 1870 during the events of the Paris Commune. Photos : ©Anaïs Costet from https://www.lemaraismood.fr/un-scandaleux-graffiti-eglise-saint-paul/

Memory links the ruins of Rocca Galliera, Revolutionary graffiti on the walls of Église Saint-Paul, the writings of Denis Diderot, memento mori paintings and Memento (2000) Polaroids. These physical vestiges speak. They ask us to continue to remember them. Most importantly, memories ask us to reflect on our own positionality within time and our own gravitational force within the warp of it.

(1). ElDante Winston’s PhD dissertation abstract.

man·i·fes·to

MIT HTC SMArchS student Jackie Xu presents their manifesto, declaring the urgency for art to take on a more active role in economics, opening up an opportunity for radical democracy.

MIT HTC SMArchS Student Jackie Xu’s essay “New Interventionist Manifesto” (2020) is a manifesto for the ages. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, manifesto derives from the latin manifestus, meaning “obvious” and manifesto, “to make public.” Indeed, Xu’s manifesto makes obvious the invisible frameworks of capitalism that undergird the art market. In their abstract, copied below, Xu gestures to a reality that has existed for decades. They critique the idea that art is a finished product, neatly wrapped and displayed, and always subjugated to the spinning wheels of the economy. Instead, as Xu argues, art resists. It pushes back against completion. It helps shape, and is always being shaped, by culture.

In its modern definition, the OED defines manifesto as:

a. A public declaration or proclamation, written or spoken;

b. In extended use: a book or other work by a private individual supporting a cause, propounding a theory or argument, or promoting a certain lifestyle.(1)

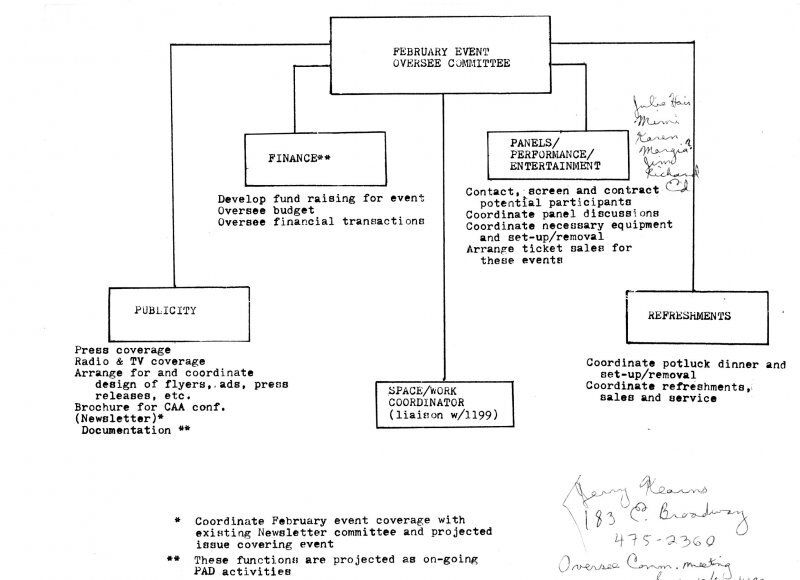

Following these definitions, the “New Interventionist Manifesto” asserts, “we regard art not as our final destination but one of the many arenas of radical intervention.” Drawing from the PAD/D and the Universal Lab, Xu demands that art should be an agent, not “a side project,” in the making of an alternative solidarity economy (Figures 1-4). In other words, art has the ability – no, the duty – to compel a radical democracy.

Fig. 1. Political Art Documentation/Distribution. Front page of Political Art Documentation/Distribution’s newspaper, issue 1. Available from: Dark Matter Archive, http://www.darkmatterarchives.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/PADD.FirstIssue.1981.No_.1.pdf (accessed December 1, 2020).

New Interventionist Manifesto

Abstract by MIT HTC SMArchS Student Jackie Xu:

The art world today has become a carnival–a theatrical organization of social risks faced by the capitalist totality. The Manifesto illustrates how the art world absorbs resistance and neutralizes threats with two cases: (1) the life and death of the self-organized artist collective Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D); and (2) the theatrical resurrection of the utopian Universal Lab in artist/activist Dan Peterman’s commissioned art project Excerpts from the Universal Lab: Plan B. The fate of these two potentially subversive projects showcases that what once threatened to contaminate the sterility of white cube ideology is now tamed with death on a pedestal and transformed into cultural and economic capital.

From left: Fig. 2. Political Art Documentation/Distribution. The non-hierarchical internal structure of Political Art Documentation/Distribution. Available from: Dark Matter Archive, http://www.darkmatterarchives.net/?page_id=72 (accessed December 1, 2020). Fig. 3. Dan Peterman, Excerpts from the Universal Lab: Plan B, Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2006. Fig. 4. Dan Peterman, Excerpts from the Universal Lab: Plan B, Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2006.

This is a manifesto for the dissidents who seek to disrupt the carnival from within, for the artworkers who see our art world today as a totality set within the larger totality of capitalism, a political economy grounded in its own renewal and reproduction. The New Interventionists go beyond tactics and tools of creative artistic disruption. We regard art not as our final destination but one of the many arenas of radical intervention. For our critical intervention to achieve its full potential, our activism should not be a symbol that can be safely encapsulated in the artwork as a final product. We need to live resistance and participate in establishing solidarity within and, more importantly, beyond the art world. We do not ask" “what can art do for a radical political economy?”; the framing of that question leaves the art world as a capitalist totality intact. It relegates “activist art/socially-oriented art” to a gestural side project. [Rather], we ask “what must art do to earn its place in an alternative solidarity economy?” This begins by thinking about how we can transfer resources to enabling structures and supportive organizations or radical democracy and learning the lessons of PAD/D and the Universal Lab.

Like art that is also evolving, Jackie Xu’s manifest is also a work-in-progress. The New Interventionist Manifesto abstract is the tip of the iceberg. In their working manifesto, Xu discusses the ways in which PAD/D and the Universal Lab can teach us about art’s agency in the building of a radical democracy.

(1) Oxford English Dictionary, “Manifesto,” https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/113499?rskey=cQyXe1&result=1#eid

Color as “Other”

A simple stroke of green paint can transform the entire meaning of an artwork. This is the magic of color. Linden examines how color evokes Otherness, Pathology, and Exoticism in European art.

Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818, Oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Domenico Cresti, Bathers of San Niccolò, 1600, Oil on canvas, Private Collection.

While 200 years separate Domenico Cresti’s Bathers of San Niccolò (1600) and Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818), color unites them. In each painting, bodies converge. Flesh on flesh, skin into skin. Hues animate. Warm yellows and reds enliven the curving, musculature of nude arms, torsos, necks, and faces. Yet, in both paintings, not all bodies are vital. Swaths of smokey greys, pasty whites, and glazes of shadowy greens render figures differently, “Othered.” Mercurial clouds, brooding shadows, and dark water enhance the moonlit sheen of each person’s form. Wet bodies glisten. The effects of chiaroscuro thrust flesh color into the focal point of each composition. We must resolve the question of body color – its evocations of life and death, health and illness, normality and abnormality – before shifting our gaze to the rest of the scene. Notwithstanding each artwork’s different historical contexts, both Cresti’s and Géricault’s paintings demonstrate the symbolic capital of color as means to signify pathology or Otherness. With a simple stroke of green or white, a normalized body transforms into alterity. This is the magic of color.

The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s book Theory of Colors (1810) is a node in this matrix of chromatic Otherness. Goethe’s book was written in a different time period as Cresti and may not have been known to Géricault. Yet, the commonalities between the two paintings and the book reflect shared conceptions of color. In his book, Goethe described “pathological colors” as a “deviation from the ordinary mode of seeing.” As he observed, for some people, red appeared blue and orange as green. Hypochondriacs frequently saw dark objects accompanied by visions of red-yellow stripes, flies, spiders, or semi-transparent small tubes. Those with ear-aches saw sparks and balls of light. Moreover, pathological vision was not just an individual experience. Goethe’s description included entire groups of people. He proclaimed:

“Lastly, it is also worthy of remark, that savage nations, uneducated people, and children have a great predilection for vivid colours; that animals are excited to rage by certain colours; that people of refinement avoid vivid colours in their dress and the objects that are about them, and seem inclined to banish them altogether from their presence.” (1) Link to source

What is powerful about Goethe’s description of pathological colors is that it implies a normal way of vision and a normal use of color. Women, savage nations, children, those with color-vision deficiency or illness are all listed under his section on pathology. Their perception and use of color did not conform to implicit conventional standards. Non-conformity meant to deviate from con-formity, to digress, deflect, or disavow the collective (“con-”) experience of “form.” Just as the predilection for color was pathologized, colors could pathologize. As suggested by Cresti and Géricault’s paintings, color could be used by artists to differentiate humans from one another. Green, grey, or white applied to a flesh mixture could evoke death, decay, or disease and bright reds could convey – quite oppositely – too much vitality, indicating the rush of boiling blood of fury or excitement.

In Aidan Flynn’s HTC SMArchS thesis “Bawdy Bathers: Locating Male Bathing Culture in Early Modern Florence,” Flynn investigates how Cresti’s painting, as well as other visual objects in early modern Italy, shed light on the real and lived experiences in which transgressive sexual encounters of sodomy occurred. He examines Cresti’s figures in detail, but also looks beyond them, considering the body’s relation to space and context. Important to Flynn’s research is the historical conception of sodomy as sexual deviance, and how such an idea manifests in paint. Among many details in the painting, deviance is represented through the deviation of flesh color from its normal color recipe. Many bodies depicted contain far too much white and grey. Color, here, is deviant. Its cultural meanings in context will be fleshed out in Flynn’s master’s thesis.

(1) Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Theory of Colors. Trans. by Charles Lock Eastlake. Project Gutenberg, 2015: 45.

Can the Artist Speak?

It all begins with an idea.

In his book Shadows and Enlightenment (1995), art historian Michael Baxandall states, “Académie lectures, with their axioms and arguments, are not very representational of the fabric of a painter’s operational reflection.”[1] Indeed, eighteenth-century art theory does not fully reflect the feelings, habits, or methods of artists who worked in the Enlightenment. Instead, it was common for scientists, philosophers, or art critics to speak for artists; theory concealed practice. Thinkers proposed formulas for how artists should draw, paint, or conceptualize their pictures. Though many artists published their own ideas about art methods, Baxandall’s statement points to a history in which an artist’s voice was overshadowed - pun intended - by the voices of others.

The discourse on “shadows” – the subject of Baxandall’s book – was one area in which an eighteenth-century painter’s “operational reflection” was neglected. Philosophers and natural scientists speculated shadow’s physical and visual properties, providing artists with epistemologically-backed suggestions on how to depict shadows on paper or in paint. From the 1740s to 1760s, the fascination for shadows as a perceptive phenomenon led to new discoveries about shadow’s color, shape, surface, reflections, and diffractions. In 1743, Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, Intendant to the King’s Gardens, read a paper at the Academy of Sciences in Paris, in which he announced his observations of the variations of colored shadow throughout the day:

“I observed in the case of more than thirty dawns and as many sunsets that shadows falling on a white surface, such as a white wall, were sometimes green but most often blue, and a blue as vivid as the finest azure.”[2]

Buffon found that during dawn and dusk, a shadow was not devoid of light but rather reflected the color of the sky, leaving a dark blue tinge. As this example shows, Baxandall’s book interestingly traces conceptions of shadows in the Enlightenment. Yet, his book falls short in fully addressing the “fabric” of an artist’s process of rendering shadows in art. As an oil painter, I felt the best way for me to critique Baxandall’s book was to put paint onto canvas, to produce theory from practice.

My artistic training is admittedly from the twenty-first century. Yet, oil paint’s chemical properties today are similar to those two hundred years ago. Oil and pigment, now and then, require certain steps of application. Fundamental to such steps is the chronology of applying darks first, and then lights. This has to do with the qualities of oil paint in which it is easier to lighten, but much more difficult to darken. In order to not lose the richness and depth of a dark color, one must paint dark pigments first. When painting a landscape, as I show, the artist may draw with blocks of shadows – geometric shapes of positive and negative space – on to which they will slowly build layers of lighter pigments. Thus, shadows, in oil paint at least, are tools in constructing composition from the very beginning. They form the crucial foundations of a harmoniously balanced scene, from landscapes to portraits. For the artist, the science of shadows is not solely based on perception, an aspect which Baxandall mainly focuses, but also based in chemistry. Art is just as much controlled by the medium, and indebted to it, as it is by the senses. Materiality sways practice, chemistry inspires shadows.

[1] Baxandall, Michael. "V. Painting and Attention to Shadows." In Shadows and Enlightenment. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. Accessed November 13, 2020. A&AePortal,https://www-aaeportal-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/?id=-13761.

[2] Baxandall, Michael. "IV. Rococo-Empiricist Shadow." In Shadows and Enlightenment. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. Accessed November 13, 2020. A&AePortal,https://www-aaeportal-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/?id=-13760.