Call and Response - Communication

After spending a couple of weeks away from the Tiny-Z, and drawing a little bit less, I realized how profoundly this experiment has impacted the way I think about inputs and outputs, and users and their machines. It is not just about the actual electromechanics of sending code to the Tiny-Z’s controller board, which sends electric impulses to the three little stepper motors that move our pencil around in space, but also what it means to communicate from digital to physical, between languages (code or spoken), and across time (designing —> building).

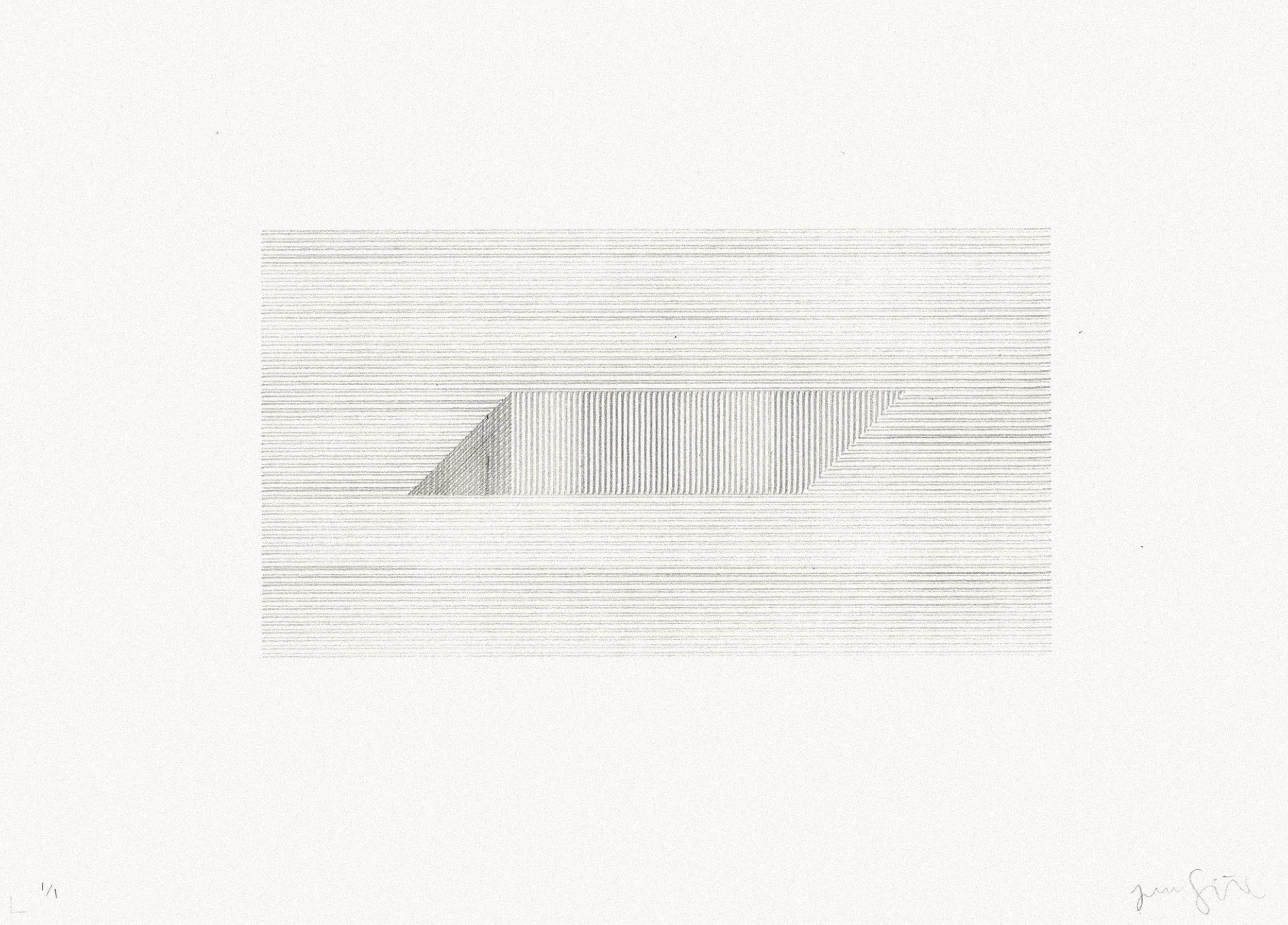

Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting, 1974. Silver gelatin print, 16 x 20 in. (40.64 x 50.8 cm.). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark

I could also use the word communication as nearly synonymous with design – both can mean future planning, information exchange, and expectation setting. And these things all come with lots of rules.

The two-sidedness of communication was the most rewarding part of drawing with the Tiny-Z. Figuring out how it alters or interprets inputs (in the form of accidents or errors) is another thing that can act as a metaphor beyond this drawing experiment, where physicality and materiality meets planning. Lines interpreted by machine and drawn on a page are not so different than plans read by builders and constructed.

Architecture’s roots in materiality are brought into tension “by the intensive use of the computer, which […] provides a natural transition towards the scientific realm since it is a machine dealing primarily with logic and calculation, a machine that has fundamentally altered the way science is practiced through tools like numerical simulation.”(Picon)

Architectural algorithms once were the tools of Vitruvius and Alberti, who used proportions to communicate and spread design ideologies (see earlier column on “Procedure”), but that kind of generalization of “good design” is much more covert today. Instead, our algorithms are embedded in the technology we use, and how we use it.

Frame enlargement from Computer Sketchpad, 1963:

“Two miles wide.” Courtesy of the MIT Museum, via Hughes “Architecture of Error.”

I would like to think that the way we use our tools has some reference to our individuality, while I am simultaneously fascinated by the impact of AutoCAD and BIM technology on the aesthetic and execution of architecture since their invention and widespread adoption. And yet, one of the chapters in Carole McCauley’s book “Computers and Creativity” (written in 1976) starts with the questions: “Can the computer see and hear? Will it talk with you?”

She continues, reminding us that “all sense organs (human, animal, computerized) operate by pattern recognition,” and that creation is “the next step beyond listening, thinking, problem solving, analyzing, or speaking.”

While there are drawing workflows involving computer generated design and code, I find something special in the simple relationship and communication between me and my machine – its feedback, errors, and accidents after all may be creativity (via serendipity), and its action is, by nature, creation. Coming back then to McCauley’s question about whether the computer can talk or hear me, I think that attuning yourself to the machine can in fact garner a human sensibility to machinic speech. The machine's feedback, errors, and accidents act as tiny, almost invisible, whispers.

References:

McCauley, Carole Spearin. 1974. Computers and creativity. New York: Praeger.

Picon, Antoine. 2008. Architecture and the sciences: scientific accuracy or productive misunderstanding? In Precisions - Architektur zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst - Architecture between Sciences and the Arts, ed. Akos Moravanszky and Ole W. Fischer, 48-81.

Fun Tangent:

OuLiPo Poetry, focused on creativity through serendipity and procedure

https://poets.org/text/brief-guide-oulipo